Throwing light on Britain’s dirty war

Posted By: May 20, 2019

Irish Echo. May 16, 2019

Mark McGovern’s book casts new light on Britain’s dirty war

Over the decades many official and unofficial reports, pamphlets, and books have been published examining the evidence for British state collusion with unionist paramilitaries in the murder of citizens.

These include reports by Amnesty International, the Barron report into the Dublin Monaghan bombings, reports by the North’s Police Ombudsman, the Pat Finucane Centre, by Canadian Judge Peter Cory; the de Silva report; and books like Ian Cobain’s “The History Thieves,” “Unfinished Business: State Killings and the Quest for Truth” by Bill Rolston, “A Very British Jihad” by Paul Larkin, and “Lethal Allies” by Anne Cadwallader, among many others.

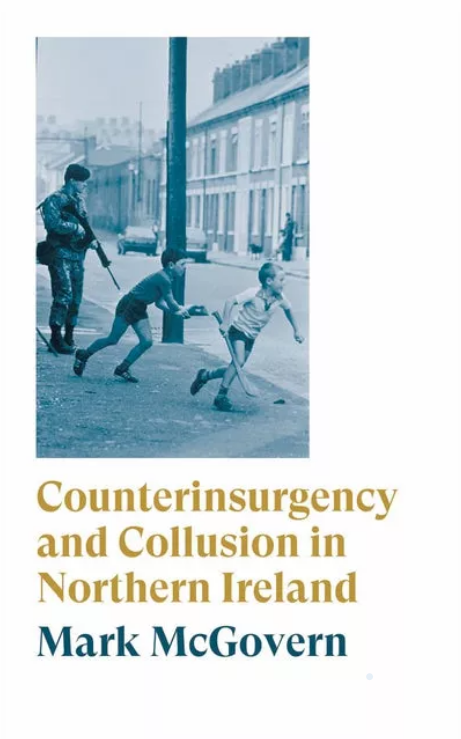

Last week, Mark McGovern’s “Counterinsurgency and Collusion in Northern Ireland” was published. It significantly adds to the body of evidence already available about Britain’s dirty war in Ireland, and its use of unionist death squads and shoot-to-kill actions.

McGovern’s book is hugely detailed and provides countless sources for the evidence it produces and the conclusions it draws. It acknowledges that there is not a “single cause of such institutional collusion” but rather a “confluence of forces.”

“Counterinsurgency and Collusion in Northern Ireland” details the various phases of organization, structure and tactics that Britain’s counterinsurgency strategy and use of collusion went through from the early 1970s until the late 1990s.

It examines Britain’s “intelligence-led attritional strategy that generated a grey zone of official deniability around the criminal actions of state agents and informers designed to defeat an intractable enemy.”

The book looks at the history of Britain’s imperial use of counter-insurgency as it sought to dominate its colonial possessions and the role of three former British army officers who promoted the use of “irregular warfare.” They were Charles E. Callwell, Charles Gwynn and Frank Kitson.

Callwell is especially interesting. He was an “Irish Unionist” who in 1896 wrote “Small Wars: Their principles and Practice.”

The British army’s current counterinsurgency field manual acknowledges that this was the start of the formal use of counter-insurgency strategy by Britain.

For Callwell, counterinsurgency was the strategic use of violence against “lesser races” and “savage enemies” and those insurgents who “dog the footsteps of the pioneers of civilization.”

As McGovern states: “Callwell was a stout advocate of a strategy of ‘butcher and bolt’ raids undertaken to destroy crops, livestock, and buildings, to raze whole villages to the ground and lay waste to conquered areas that fanatics and savages [could be] thoroughly brought to book and cowed … [so that they would not] rise up again.”

McGovern also looks at how collusion, and the sharply dividing opinions of how it was used in the North, impacts today on the “often political divisive debates about how to deal with the legacy of the past and outstanding issues of truth and justice left in its wake.”

While the primary geographical focus of this book is East Tyrone and South Derry – Mid Ulster – the book also looks at the role of the Military Reaction Force (MRF) in sectarian killings in Belfast; the emergence of the Force Reconnaissance Unit (FRU) which ran Brian Nelson and other agents and was responsible for the murder of Pat Finucane; and the import of weapons from South Africa in 1987 with the knowledge of British intelligence.

It is worth remembering that the human cost of this weapons shipment can be found in the numbers killed in sectarian attacks. In the three years prior to receiving this weapons shipment unionist death squads had killed 34 people. In the three years after the shipment, they killed 224 and wounded countless scores more.

Ulster Resistance, which was founded by the DUP in 1986 played “the most critical part in the operation” to bring the weapons into the North.

Looking at Mid Ulster McGovern states: “Between 1988 and August 1994 86 people were killed in East Tyrone … many with guns imported as part of the 1987 arms shipment.”

Many of these were IRA Volunteers, Sinn Féin activists or their family members.

All of this has to be seen in the context of the objective of the British state and the British army, especially during the Thatcher years. In its report on Operation Banner, the name given to the thirty years of Britain’s War in Ireland, it states: “The British government’s main military objective in the 1980s was the destruction of PIRA, rather than resolving the conflict.”

Collusion involving unionist paramilitaries was also interconnected to shoot-to-kill operations by British forces.

McGovern states: “…collusion should not be seen in isolation but rather viewed in relation to broader state counterinsurgency – particularly evidence of a shoot-to-kill policy, conducted primarily by specialist units of the RUC and British Army, directed against republicans.”

In East Tyrone between 1983 and 1992, 26 IRA volunteers were assassinated, including eight at Loughgall, along with one civilian.

McGovern reviews many of these events in detail. He also examines the circumstances surrounding the killings of Gerard Casey, Liam Ryan and Michael Ryan in the Battery Bar, Ardboe; Malcolm Nugent, Dwayne O’Donnell, John Quinn and Tomas Armstrong in Cappagh; Sinn Féin councilors John Davey and Bernard O’Hagan; Kathleen O’Hagan, Tommy Casey and Patrick Shanaghan, and, sadly, many more.

McGovern’s book begins and ends its examination of individual cases with the murder of Roseann Mallon 25 years ago on May 8, 1994.

At the time of the attack on her home it was under constant surveillance by British army covert units, who were in “constant, direct contact with an officer at their base who was overseeing matters.” There were also cameras relaying images to a nearby base “home to British Army specialist units such as the Special Air Service (SAS).”

At the inquest it was revealed that evidence “had not been provided, disappeared, been lost, tampered with or destroyed by the policy – including suspect interview notes, police officers’ notebooks, and last but by no means least, the wiped video footage taken from the covert British post on the day of the killing…Getting to the truth was also hindered by the refusal of some former policemen, servants of the law to co-operate with the court and the lengthy, drawn-out battles to overcome official barriers put in the way of disclosure.”

In his conclusion, McGovern addresses the claim of a witch-hunt by former British military personnel and the unionist and Tory parties and media. He concludes that “the record rather suggests a long-term de facto immunity and a priori amnesty for military wrongdoing.”

“He notes that “only four British soldiers were convicted for murder in the North of Ireland …in each case the soldier in question served less than three years in jail before being released and returned to the ranks of the British Army.”

“Counterinsurgency and Collusion in Northern Ireland” adds significantly to our knowledge of how this British military and political policy worked.

It provides much new sourced detail. It also gives an important insight into why successive British governments have constantly blocked progress on legacy issues.