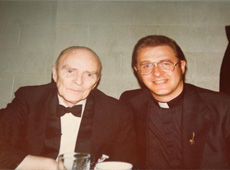

SDLP titans John Hume and Seamus Mallon split on issue of Irish unity

Posted By: December 30, 2016

Belfast Telegraph. Friday, December 30, 201

The party leader and his deputy, whose differences were mostly kept under wraps during their dominance of northern nationalism for much of the Troubles, were fundamentally split on the definitive issue.

The schism erupted during a meal at the Irish embassy in London in January 1986.

They had been invited, along with other SDLP members and family, by then ambassador Noel Dorr to mark MP Mr. Mallon officially taking his newly-won seat for the first time at Westminster.

In a missive – marked “secret” – sent back to Dublin, Mr. Dorr told the Irish government “considerable differences of outlook and approach between John Hume and Seamus Mallon came out quite clearly in the discussion.”

“An argument developed between them in which Hume spoke of the ambivalence of Northern nationalists about Irish unity – they want it but they know the time is not ripe for it and the concept of unity is more important as a factor in what he called ‘the tribal conflict’ than in itself,” the diplomat reported.

Mr. Hume argued that his native and predominantly nationalist Derry had closer links with Glasgow than the west of Ireland or even Dublin, according to the newly-declassified documents released into the National Archives.

“Mallon, on the other hand, disagreed with this and spoke of the desire for Irish unity as a deep motivating force North and South of the border,” Mr. Dorr said in the letter which was copied to the Taoiseach Garret Fitzgerald and Tanaiste Dick Spring.

“He also challenged Hume’s view that Irish unity, of necessity, would have to be a very long- term prospect.

“Mallon sees the Anglo-Irish Agreement as a kind of the last throw by constitutional Irish nationalism.”

The fledgling agreement had been signed just two months beforehand and was facing a revolt from unionists.

Mr. Mallon told the dinner party if it failed the outlook would be “bleak.”

But his party leader “dissented” from this analysis – insisting the treaty which gave Dublin an advisory role in Northern Ireland was a new beginning rather than a last opportunity.

Mr. Hume argued that a substantial number of Northern Catholics would never support violence in any circumstances, and agreed with a suggestion that there would be “another agreement if the Anglo-Irish Agreement failed.”

The pair also appeared to differ on what direction the SDLP should take in the immediate aftermath of the agreement.

Mr. Hume said the choice was to “play it safe” by appealing to their own supporters or to reach out to unionists to resolve the “fundamental historic problem.”

He strongly favored reaching out to unionists and wanted to do it sooner rather than later.

But Mr. Mallon had a “longer timetable in mind” and said his voters – many of whom gave him conditional support – were giving the agreement a chance and wanted to see it delivered.

In the letter, Mr. Dorr appeals for discretion around his report as he was sure neither Mr. Hume nor Mr. Mallon would appreciate having their differences talked about.