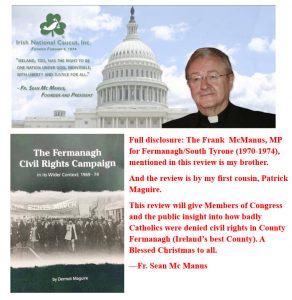

Patrick J. Maguire Reviews “The Fermanagh Civil Rights Campaign”

Posted By: December 19, 2023

Recollections of Fermanagh society in the 1960s and earlier decades is now limited to those, including this writer, who have passed the three score and ten. Others, despite what they may have read, seen or been told, will not have the same understanding of what life was like back then. General accounts and summaries give some idea of the inequalities that existed but to get a good understanding of why so many, mostly those of the Catholic/nationalist population, felt deprived of their entitlements one needs detailed accounts of the arrangements of the Unionist regime that prevailed and explanations of why and how the system had been so thoroughly and carefully developed and methodically implemented.

How great was the challenge of overcoming and dismantling the discriminatory governing arrangements, at all levels, may be difficult to appreciate without detailed, comprehensive insights into what transpired in the later years of that regime.

Such an account is now available in the excellent “The Fermanagh Civil Rights Campaign,” the book that Dermot Maguire has published after years of research, guided by memories from his own involvement, as a student, in Peoples Democracy, one of the more radical branches of the Civil Rights movement. An experienced historian, Dermot is aware of the importance of providing a clear and easily understood context. Indeed, the subtitle of his work is “in its wider context: 1969– 74.” He does not restrict the setting, however, to those years. He clearly explains how we arrived at the situation that pertained in the 1960s by skilfully tracing developments in Fermanagh and across all Northern Ireland from “the shock of partition” in 1921. In doing so, he clearly shows how gerrymandering, unfair allocation of housing and discrimination in employment, especially in local government, was used to safeguard Unionist rule or, as he calls it, “misrule.”

In looking at the practices which ensured that Catholics/Nationalists were kept as powerless as possible, with many being forced to emigrate, he touches on the roles and attitudes of some of the leading Unionists of those 40 years such as Basil Brooke. He shows how the best efforts of Catholic representatives like Cahir Healy and Canon Tom Maguire were ineffectual in bringing the attention of members of the British Government to the situation here.

In 1947, however, something that would be of significance did happen – the passing of an Education Act that would apply to all parts of the UK. By the mid-1960s, the consequences were beginning to show in the higher standards of education among an increasing number of young Catholics. University access was no longer restricted to a tiny minority. It was no coincidence that many of the young, articulate and able leaders of the Civil Rights campaign had benefitted from the higher education available to their generation.

Dermot takes a closer look at the years from 1962 to 1967, a time when society was undergoing great change across the western world. In this part of Ireland, several groups and individuals began to campaign for civil liberties. He summarizes the contributions of the Council for Civil Liberties, the Liberal Party (through their one MP, Sheelagh Murnaghan), the Homeless Citizens League, the Campaign for Social Justice, led by Patricia and Conn McCluskey, the N.I. Labour Party, the Campaign for Democracy and, in Derry, the Housing Association and the Housing Action Committee. Coming to the fore in those years were activists such as Gerry Fitt, elected as MP to Westminster in 1966, and Eamon McCann. By then, Television was providing a new way of making people aware of the wrongs in our society. It would become more and more important as the Civil Rights Movement developed.

Of course, not all who rose to prominence in those years were advocates of equality and fairness nor were all the bodies established at that time promulgating the cause of Catholics. A young, charismatic preacher named Ian Paisley was becoming well known. He set up the Ulster Constitution Committee and established the Ulster Protestant Volunteers. The Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) was reconstructed. Attempts by the Unionist Prime Minister, Terence O’Neill, to introduce reforms met with stiff resistance – resistance that he was unable to overcome.

The main foci of Dermot’s work are, of course, the Civil Rights Association established in June 1967 and the various groups that came to exist under its broad umbrella, particularly those who were active in Fermanagh. Events of 1968 and early 1969 were particularly important. The occupation of a Council house in Caledon, as a protest against unfair allocations, and the subsequent march from Coalisland to Dungannon is summarized. The march in Derry on October5th, when the participants were ruthlessly baton-charged by the RUC, the birth of Peoples Democracy and the walk that its young, mostly student, members led from Belfast to Derry, with the infamous ambush at Burntollet, and other protests in Armagh and Newry get the author’s attention. By Chapter 4, he concentrates on Fermanagh and in it and the 2 subsequent chapters, Dermot provides extraordinary details, many long forgotten, even by those of us who were around back then, of how the Fermanagh Civil Rights Association (FCRA) was set up, its tactics, the differences and tensions with Peoples Democracy, the events it initiated, how the authorities reacted and those who were most active in the several protests. The account of the inaugural meeting on Monday February 10th, 1969 – in St Ninnidh’s Hall in Derrylin, as permission to use Enniskillen Townhall was refused, — is covered in detail, with quotations from those who spoke there that night.

Many younger people may be surprised to learn that the first chairman of FCRA was a Protestant, as was another of the 17 members elected to the original committee. Several of those who spoke, with remarkable eloquence, at that inaugural meeting were students who had been at Burntollet five weeks earlier. When Terence O’Neill called a surprise election for February 24th, three of those went forward for election to the Fermanagh constituencies. The rapid pace of what was developing was an indication of how things were going to proceed over the next couple of years.

Though the election did not produce any new MPs for Fermanagh (As was normal then, 2 Unionists and 1 Nationalist were returned), it was a watershed occasion in the political landscape of The North. With Civil Rights leaders Hume, Cooper and O’Hanlon elected, the Nationalist party losing its leader and ‘Big House’ unionism shaken by a weakened O’Neill, the political scenery was shifting. An idea of the detail that Dermot provides can be gathered from some of the subheadings that he uses – Fermanagh’s First Civil Rights March, Large Omagh Civil Rights Rally, FCRA Paget Square Rally, Bernadette Devlin Elected MP, Riots in Derry, One Man One Vote, O’Neill Resigns, Occupation of the Arney Council House, A Newtownbutler Housing Delegation, Another Housing Scandal – in Fairview Enniskillen, Occupation of a Lisnaskea Council House, The Newtownbutler to Belfast Housing Cavalcade, The Kilmacormick Detainees and The Publication of Fermanagh Facts. And all of these and more took place within a few months. The very informative, influential and awareness-raising Fermanagh Facts, put together and issued by Colm Gillespie (the first secretary of FCRA) and Frank McManus is, as Maguire says, “to this day, a devastating record of planned injustice against the Nationalist/Catholic majority population of the county –in housing, jobs and franchise over a long period.”

There is much, much more in this extraordinary work than it is possible to mention in this review. Events were developing on several fronts at an accelerating rate as 1970 arrived. By then, Frank McManus was chair of the Fermanagh Civil Rights Association and had become its leading figure in the county. He led the occupation of the Council Chamber in Enniskillen Townhall, a march through Enniskillen, and the take-over and barricading of the Council offices in East Bridge Street. This resulted in a charge of ‘trespass in a public building’ being brought against him, Councilors James Donnelly (Enniskillen) and James Lynch (Roslea) and 27 others.

The Civil Rights movement in Fermanagh peaked in June 1970 with the selection of McManus as a Unity candidate for a forthcoming election to Westminster. With those who could have split the Nationalist vote withdrawing, the Unity candidate won the seat, defeating the sitting MP, the Marquis of Hamilton by 1,423 votes and joining another Civil Rights activist, Bernadette Devlin, who was elected for Mid-Ulster, in the London parliament. (Gerry Fitt was already there – since 1966). Again, Dermot covers these developments in detail and quotes at length from McManus’s early speeches as an MP.

By October 20, Fermanagh men who had not paid the fines imposed for the occupation of the Council offices were in Crumlin Road Prison. This prompted further protests. A meeting on the Diamond was attended by several Civil Rights leaders, including John Hume, Ivan Cooper, Austin Currie and Paddy Devlin. By then, they and others had formed The Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP). The SDLP decided not to support a march in Enniskillen on November 28th – an event deemed illegal under a 6-month ban introduced in July on all marches. It, like the other events organized in Fermanagh, passed off peacefully. Nevertheless, in January, 42 of those involved were sentenced – 41, few of whom were present, had fines imposed, ranging from £7 to £22. Frank McManus, now the MP for Fermanagh/South Tyrone was imprisoned for 6 months.

And so, the protests continued but the unity of earlier times no longer existed. The more radical and left-wing Peoples Democracy had parted company with the official civil Rights Association (NICRA), divisions between those who were ‘Nationalists’ and those with more Republican views had become greater. The SDLP came to be seen by many as a middle-class party. However, other developments were to have much greater impacts and would change the focus of all from the peaceful events of the Civil Rights Association. On Monday August 9, 1971, Internment was introduced. (12 Fermanagh men were ‘lifted’.) Four days later, Enniskillen experienced its first violence – in what Dermot calls “The Night of Broken Glass.” Incidents occurred in Belcoo and Newtownbutler. More activists were summonsed. One of the speakers at the Enniskillen meeting, Thomas McDowell, from Birmingham, was sentenced to 6 months imprisonment for behaviors likely to cause a breach of the peace. As violence became more widespread across The North, many supporters of the peaceful movement began to withdraw. A Civil Disobedience Campaign got underway. Other groups were formed. Frank McManus became chairman of The Northern Resistance Movement, whose members included Bernadette Devlin and Michael Farrell. But our world was changing even more rapidly and drastically as shootings and explosions became frequent. Then, on Sunday, January 30th, 1972, 13 men, at a march in Derry, were shot dead. While all the peaceful protests and marches had brought about several reforms in local government, they had failed to seriously damage Unionist rule. The actions of the Parachute Regiment on Bloody Sunday brought it to an end. Seven weeks after the 13 deaths, Stormont was “prorogued”–abolished. January 30, 1972, is seen by some as the end of the Civil Rights movement. More marches and demonstrations took place, most notably one in Newry on Sunday, February 6th, attended by as many as 50,000, but these were now responses to Internment and the Bloody Sunday deaths.

Dermot devotes his last chapter to Rights and Politics in a Time of Trouble: May 1972 – May 1974 and summarizes his own views on what happened during the momentous years he has written about in a 5-page Conclusion. His Appendices are rich sources of information. For example, you will find there long lists of names of those brought to court for various protests and for those who participated in The Rent and Rates Strike that was part of the Civil Disobedience that followed Internment. There too, one will find short but insightful descriptions of what are often referred to but seldom explained, e.g., The Special Powers Act, The Downing Street Declaration, The Macrory Report and The Scarman Tribunal. While Dermot Maguire’s work is, necessarily, factual in places, it is well written and easy to read. Most importantly, it is essential reading for anyone, irrespective of their political affiliation, who wants to have a better understanding of the events of the late 1960s, in Fermanagh and further afield, of all that happened in such a short time and the reasons why. For those of us old enough to remember those momentous days, it has reminders of so much, particularly of those who were involved in what, initially, were heady, exciting days. It also leaves the reader with regrets – regrets that what was a peaceful movement trying to achieve equality for all citizens of this part of Ireland was met with such resistance by those who wished to maintain what they believed was their rights to political discrimination and superiority.

Patrick J. Maguire

December 7, 2023

“At some point in a country’s history there are enough people who feel the same way at the same time to create a force and to change the pattern of events. That’s what happened in Northern Ireland in the autumn of 1968.”

Bernadette Devlin: The Price of my Soul (1969)

All proceeds from the book go to Palliative Care Fermanagh and Air ambulance NI.

Copies are available in Waterstones and in several local shops throughout the county.