Irish National Caucus and Jimmy Carter

Posted By: February 23, 2023

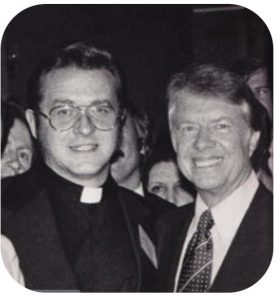

Fr. Mc Manus and Jimmy Carter, Pittsburgh Hilton Hotel, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. October 27, 1976.

Irish National Caucus and Jimmy Carter

By Fr. Sean McManus

While I was based in Boston, I organized, with the key help of the late Massachusetts State Senator Joe Timilty, who worked in the Carter campaign, a meeting with Jimmy Carter and the Irish National Caucus.

I brought 34 Irish-Americans from all across the United States to Pittsburgh, PA, to meet with the presidential candidate on October 27, 1976—just six days before he was elected president.

Professor Paul Power stated: “The Irish National Caucus … achieved its first major mark … when it obtained an “Irish justice statement from candidate Jimmy Carter.”

The significance of that assessment is all the more apparent when it is realized that in the 1970s, Professor Power of the University of Cincinnati, was “the only American political science academic researching Northern Ireland affairs.”

I made the opening statement, and in his response, Jimmy Carter said these key words: “We see or come on the evening television news and in the national headlines every now and then, specific instances where human rights are subjugated and where quite often our nation as was pointed out by Father [McManus], stands mute and doesn’t speak. …it is a mistake for our country’s Government to stand quiet on the struggle of the Irish for peace for the respect of human rights and for unifying Ireland.”

Rather than “re-write” the story, let me give a quote from my Memoirs: My American Struggle for Justice in Northern Ireland. (Third U.S. Edition, 2019. Page 127-140).

CHAPTER 10. THE CAUCUS AND JIMMY CARTER

Needless to say, we were delighted by that statement. And the British were not. The Guardian, supposed to be a moderate and reasonable paper, sniffed in an editorial: “And now, a few days from what may be his elevation to the Presidency of the United States, along comes Jimmy Carter, sharing a platform with Seán Mac Stíofáin’s confessor and pledging himself to a United Ireland.”

Carter was roundly condemned by the British media and by British and Unionist politicians. Mr. Roy Mason, the British Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, told the House of Commons that Carter was “giving aid and succor to Ulster terrorists.” Nothing surprising there.

FitzGerald rallies to Brits

What would surprise many Americans (but not this Fermanagh man) was the hysterical reaction of the obsequious Dublin government of that time. The Boston Globe would later report: “Irish embassy officials protested vehemently to Carter aides. Carter, under pressure, agreed to send a telegram of clarification … Carter, the next day, telegrammed Irish Foreign Minister FitzGerald”: “… I have been informed that certain news reports concerning my meeting yesterday with Irish-American leaders have misrepresented both my position and my statements … I do not favor violence as part of a solution to the Irish question.”

No one, of course, had reported Carter had favored violence. But this was a classic Dublin government tactic—scare people from speaking out for justice in Northern Ireland lest they be accused of supporting violence. It was unconscionable to do that to Carter. Yet, the media establishment in Ireland never objected to FitzGerald’s inexcusable and disgraceful actions. Years later, when candidate Bill Clinton, on April 5, 1992, in New York City, made promises to a group of us (some who also had been at the Carter meeting in Pittsburgh), the huge difference was that Taoiseach Albert Reynolds welcomed Clinton’s statement—and the rest is history.

I am haunted by this thought: Had FitzGerald welcomed Carter’s statement, how much sooner the peace process could have started, how many lives might have been saved, and how so much suffering could have been spared? And I am not alone in thinking this way. Well-known author and journalist Tim Pat Coogan says in his memoirs, “During the 1974—7 coalition period, the voice of the Dublin component of the Toffs” Brigade [pro-British elite] was particularly strong, powerful, and continuous. I would blame Dublin’s attitude in these years for helping to create a mindset that deepened the political vacuum and helped to prolong the Troubles.”

End of Memoirs’ quote.

Final comment on the deplorable Garret FitzGerald.

In his most recent book, prolific and very brave Dublin writer, David Burke, relates a revealing anecdote about FitzGerald. His book is An Enemy of the Crown: The British Secret Service Campaign against Charles Haughey. Mercier Press. Cork. 2022.

The book tells the reader (page 273) about Daphne Park, who in 1960 was the Head of MI6 in the Congo and was allegedly involved in the assassination of Prime Minister Lumumba. In 1982, Maggie Thatcher appointed Park to the BBC Board of Governors. (Shocked, shocked, I tell you, that Maggie Thatcher would appoint an alleged assassin!)

In 1979, Park retired and very conveniently got a job at Sommerville College, Oxford. And, even more conveniently, she then became the organizer of the British-Irish Association (BIA). In October 1979, Maggie Thatcher pulled out of retirement the former Head of the entire MI6, Maurice Oldfield, appointing him Northern Ireland Security Coordinator. Naturally, old chap, Oldfield would turn to his former spook-colleague Park for intelligence on the Irish politicians in the BIA.

It so happens —again very conveniently—that Park had “befriended” Garret FitzGerald.

The book informs us that Ms. Park would always refer to FitzGerald as “Dear Garret.” Well, as a Fermanagh man, I say, “She would, wouldn’t she?” After all, she was MI6, and whereas she would have known Charlie Haughey was an enemy of the Crown, she would have also known that “Dear Garret” was, indeed, a friend of the Crown—perhaps one of the best friends in over 850 years—and counting—that England ever had in its oppression and control of Ireland.

God bless Jimmy Carter, and God save Ireland from the likes of Garret FitzGerald and his fellow travelers.