How old ghosts are haunting Ireland

Posted By: March 27, 2018

How old ghosts are haunting Ireland

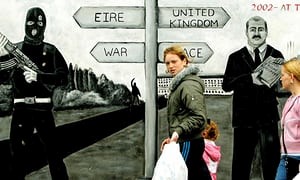

As Britain prepares to leave the EU, the Irish border question looms ever larger, stirring fears that the Troubles have not yet been consigned to the past

by Susan McKay. The Guardian. London. Sunday, March 25, 2018, The taxi was a big German four-wheel-drive affair, and as I got into the back seat, I thanked the driver for his willingness to make the journey. The “beast from the east” was due to collide with Storm Emma and, south of the border; the government had warned people that a blizzard was imminent, that they should get home by 4 pm and stay there. It was 4 pm and I was in Belfast. I’d traveled up on the early train from Dublin, where I live, to report on a trial.

I emerged from the court to a demented sky and the news that public transport north and south had been suspended. I needed to get home. It took a few calls to get a taxi company willing to agree on a fixed fare. As I settled into the cream leather upholstery, the happed-up driver looked back at me in his rearview mirror and said: “I know who you are. Do you know who I am?”

I had not heard of him for many years. He’d been one of the leaders of the Loyalist Volunteer Force, the paramilitary faction responsible for a series of sectarian murders in County Armagh, about which I had written in the 1990s. Its origins were in the Ulster Volunteer Force, originally set up in 1912 to defend against home rule for Ireland. Back then it was trained on the lawns of the stately homes of the gentry, its guns stored in their attics when its members went off to fight in the first world war. They were led by men like Viscount Brookeborough who, as the Anglo-Irish treaty of 1921 was negotiated, revived a militia, ready to ensure that not an inch of the new Protestant unionist state north of the border would be yielded to the Catholic Irish state south of it. This force became the Special Constabulary, including the “B” Specials. The modern UVF, formed in 1966, had throughout the Troubles backed the Rev. Ian Paisley’s hardline stance, and the taxi driver’s faction had continued to do so, rejecting the Good Friday Agreement. The current leader of the DUP, Arlene Foster, had also rejected the agreement and defected from the Ulster Unionists to join Paisley’s party. But Paisley had turned. In 2007, he had taken power as the first minister alongside former IRA leader Martin McGuinness.

My driver was said to have been the LVF’s quartermaster, the man who supplied the weapons. He said he was pleased to meet me. We sped out of the city and down the road, stopping at a filling station where he bought me a bottle of water. He said there had been a lot of people very annoyed about things I had written. But he believed in a free press. You could not say you believed in free speech and then try to muzzle the journalists.

Women dance alongside an Orange Order march in Belfast, 1971. Photograph: Ray Bellisario/Popperfoto/Getty Images

The LVF supported the Orange Order in its efforts to “reunite the Unionist family” by insisting on the right to march through Catholic areas. I recalled seeing one of its footsoldiers kicking a notebook out of the hands of a reporter who had just asked him a question. Unionists told us continually that we never spoke with them, and never told the truth about them. I asked a young man once about an ugly incident. He denied it had happened. I said it had been shown on television. “That’s because the TV cameras are against us,” he replied.

We passed the road into Hillsborough, whose castle is official residence to the Queen and the secretary of state, and thus rarely occupied. I had interviewed the leader of the driver’s faction, Billy Wright, in a house in the village. He called me “dear,” and I was given tea in a china cup. Once, I was given a police briefing about him. Among other, more substantive things, I was told he used to whistle the Sash, the Orange Order’s strutting song while being interrogated. But a few years later, when I looked for another briefing, the first was denied, and I wondered about the information I had got anyway.

I had gone to Wright’s trial. He shouted at the judge convicting him that he was a “Fenian bastard.” King Rat, as Wright was known, was murdered in HM Prison Maze in 1997.

We passed by places where there had been atrocities. Bushkill Road, where in 1975 the Miami Showband had been stopped at a fake checkpoint by the gang that included precursors of the LVF along with members of the Ulster Defence Regiment. This was the local branch of the British army set up to replace the by then notoriously sectarian B Specials.

The driver talked. Told me he’d been shot, twice, both times by loyalists. He denied he had supplied the gun for the murder of a Catholic taxi driver, as claimed in a book. The killer of the taxi driver had been a tout, he said. I remembered the man’s wife, pregnant when he was murdered, his parents publicly forgiving the killer. As the driver spoke, I remembered many things I used to know. He told me things I had once wanted to find out. Most of the people we talked about are dead. This was no longer journalism, but history under thin, but deepening, ice.

I asked about the present. I’d heard loyalists were now taxing drug dealers. It was more or fewer gangs now, he said. He took no part in it anymore. He voted DUP, like everyone else, but they were useless at negotiations. Motorway signs flashed red warnings. The blizzard intensified as we traveled south and snow was beginning to drift across the motorway. The driver was unfazed. He knew the roads.

“I love Dublin,” he said. He came down often, sometimes with his wife for weekends at the Shelbourne. This is a beautiful, expensive hotel on St Stephen’s Green, where the Anglo-Irish gentry once stayed when in town. There are bullet marks in the walls from exchanges of fire during the 1916 Easter Rising, when British forces fired from inside, and the Irish Citizen Army attacked from the Green. The 1937 Irish constitution, with its claim to ownership of the six counties of Northern Ireland, was drafted in it. The driver dropped me at my house. I thanked him, paid, wished him a safe journey home. We shook hands. He said it had been good to talk, and I said yes and stepped out on to the treacherous pavement.

Catholic children play with toy guns under an IRA mural in south Belfast. Photograph: Peter Morrison/AP

“We mean to stand by Britain and the empire.” That’s a quote from a YouTube clip posted on Twitter a couple of weeks ago by Ian Paisley junior. (He’s 51, but his late father casts a long shadow.) The speaker, in 1940, was a largely forgotten figure called John Andrews, who was briefly prime minister of Northern Ireland. He denounced the wartime neutrality adopted by Eire, as the south of Ireland was then known. Paisley also tweeted a clip from the following year of haughty Brookeborough, who replaced Andrews and was prime minister for 20 years. He spoke of his determination that Ulster would be to the fore in “the struggle against Nazi aggression.”

The DUP is going backward in time. When there is a crisis, as there is now over the Irish border, unionism reminds Britain how much it owes to loyal Ulster. Paisley junior recently urged the Brexit secretary to stand up like a man and take a “no surrender attitude” to the EU, the reference being to the valiant cry of the Protestants besieged in Derry by Catholic forces in 1689. While the Republic commemorated the centenary of the 1916 Easter Rising, the DUP invoked the “sacrifice at the Somme” made by thousands of Ulster soldiers in 1916. It got exercised all over again about the old nationalist slogan, “England’s difficulty is Ireland’s opportunity.”

Brexiter Michael Gove made a ministerial visit to Ballymena on the gallant edge of the empire earlier this year when Paisley hosted him as guest speaker at a fundraising dinner in his North Antrim constituency. Gove shared the DUP’s view of the Good Friday agreement from the start – that it appeased the IRA and was akin to supporting Nazism. He supports the DUP’s demand that Northern Ireland must exit the EU on exactly the same terms as the rest of Britain – a recipe for a hard border. This is incompatible with the commitment Theresa May was forced to make to the EU and Ireland to uphold the Good Friday agreement. The DUP and its Brexit allies are willing to poke the embers of old resentments over Ireland’s failure to fight Nazi Germany to fuel antagonism towards Ireland and the EU today. German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s assurances to the Irish Taoiseach, Leo Varadkar, of her “unconditional support” for Ireland’s position on the border, will feed the fire.

At the dinner, Gove praised the historic work of the RUC and the PSNI, which replaced it. The RUC was almost entirely Protestant and as part of the peace process one of the recommendations made by Chris Patten, who chaired the independent commission on Policing for Northern Ireland, was that 50:50 recruitment quotas be introduced to increase the number of Catholic officers. Though targets had not yet been met, the policy was abandoned in 2011 by the then Tory secretary of state for Northern Ireland, Owen Paterson. He recently attracted fresh controversy by retweeting an article that claimed the Good Friday agreement had “run its course.”

The DUP has devoted itself in recent years to staunchly protecting the record of the security forces in Northern Ireland from legal scrutiny, particularly in relation to allegations of collusion with loyalist paramilitaries, about which disquieting evidence continues to emerge. In the absence of structures to deal with the past, baroque conspiracy theories proliferate. In this way, though they are over, the Troubles keep getting worse.

Unionism is a politics of vigilance, of defending the frontier, standing tall against the cowardly enemy in the bushes. The IRA murdered hundreds of the police and the UDR, many in the border counties. Every day is the anniversary of at least one Troubles murder. Last week’s included that of a young woman who was sitting with her boyfriend in his car outside her family home, a border farmhouse, when the IRA attacked, riddling the car with gunfire. It claimed the target was her finance and that he was in the UDR but he was not, and the killers knew it. I interviewed her still devastated mother a few years ago. The family had left their farm and retreated to a village.

It was a pattern. Unionists called it genocide and ethnic cleansing. Arlene Foster’s father, a farmer and part-time policeman, was wounded in such an attack. The family moved back from the border to a town. Unionists accused the Irish government of harboring the terrorists, and the British government of failing to provide adequate security. At one stage former DUP leader Peter Robinson entertained the possibility of fencing the border.

There has been a reluctance to let go the notion that the IRA remains a threat. Earlier this month Paisley issued a statement condemning an incident in which he said a suspected booby trap device had exploded under a policewoman’s car. “Terrorism will never prevail,” he declared. It quickly emerged that in reality, the car had caught fire because of an engine fault.

Days after he was retweeting the voices of somber unionist grandees of the past, Paisley was posting grinning selfies with Ivanka Trump on his way to a private dinner with the presidential family. St Patrick’s Day in Washington turned male politicians from both sides of the border into fawning sycophants around Donald Trump in the White House. (The Taoiseach, Leo Varadkar, was the most craven.) Saint Patrick’s Day used to be celebrated largely by nationalists in Northern Ireland with much waving of the Irish flag, the tricolor. In 1999 Belfast’s city council refused to fund the parade. However, in 2013 a DUP politician decreed that St Patrick was no Catholic – he was an evangelical Protestant, “God’s man for Ulster.”

Tony Blair and Bertie Ahern sign the peace agreement. Photograph: Dan Chung for the Guardian

Paisley and half a dozen other DUP politicians romped freely. Gerry Adams was off being lionized in New York. Paisley boasted about his longstanding connections with Trump and claimed unionism had upstaged Sinn Féin and the Irish government. He posed in front of Andy Warhol’s 1977 portrait of Queen Elizabeth in the British embassy. The DUP invited Trump to Northern Ireland, and weirdly, the Taoiseach invited him to the Republic to view the border. He may well suggest a wall.

Also attending events in Washington was David Sterling, head of the Northern Ireland civil service, which is currently running departments without ministers. According to Paisley, he gave an upbeat account of the Northern Ireland economy. Sterling had traveled to the US shortly after he gave evidence to the inquiry into the disastrous renewable heating initiative, which has cost the exchequer an estimated billion pounds, the same price as May promised for the DUP’s 10 Westminster votes. Arlene Foster’s ministerial role in the matter is under scrutiny – she maintains she is innocent of any wrongdoing.

The inquiry is finding a lack of documentary evidence with which to test conflicting assertions about responsibility for decisions. Sterling admitted civil servants had facilitated Stormont ministers’ desire for confidentiality by desisting from taking minutes at meetings, in case freedom of information requests were later made. Both Sinn Féin and the DUP are implicated in this.

The British and Irish governments have been complicit in this refusal of accountability, though they are co-guarantors of the Good Friday agreement. Faced with local intransigence they have, over the years since 1988, apparently given up on any idea of shaping the Good Friday agreement, instead of becoming facilitators of whatever the Northern Irish parties would agree. The higher purpose of bringing about reconciliation between ghettoized and wounded communities was left aside.

Among the leprechaun suits and colleen dresses for hire on St Patrick’s Day from Belfast’s costume shops this year, there were crocodiles in various shades of green. In 2017 the DUP alienated moderate nationalists as well as Republicans by comparing yielding to their demands to feeding an insatiable crocodile. The DUP leader had previously spoken about the need to guard against “rogue” and “renegade” ministers from Sinn Féin and the SDLP.

In the elections that followed, Unionism lost its majority at Stormont for the first time in the history of the Northern state. It also lost the ability to use a mechanism designed to protect minority interests, which it routinely abused to block legislation on, for example, same-sex marriage and abortion rights. The DUP insists it will not tolerate the creation of a Border in the Irish Sea, but it has itself essentially already created one, to protect biblical Ulster from the modern world. No wonder Foster pushed for direct rule by a parliament in which her party holds the prime minister hostage – Sinn Féin does not take its seats at Westminster, and almost everyone else scrambles for the doors when a Northern Irish issue comes up.

Almost like the good old days. Before the eruption of nationalist rage that marked the beginning of the Troubles in the late 1960s, unionists had their own parliament at Stormont. They ruled from its halls of marble and mahogany without meaningful internal opposition, since they had gerrymandered electoral boundaries, and undisturbed by Westminster since there was a gentleman’s understanding that Northern Ireland issues would not be raised. Tom Paulin has a poem called “Of difference does it make,” which is prefaced by a note explaining that during its 51 years of existence only one bill sponsored by a non-Unionist was passed. This was the Wild Birds Protection Act of 1931, and the poem is about a wild bird called the not a whit: “… it raps out a sharp code-sign/like a mild and patient prisoner/pecking through granite with a teaspoon.”

The BBC in Belfast was compliant, assuring ministers that they should “look upon us as their mouthpiece.” They duly declared themselves upset if Irish music was broadcast and had the reporting of Gaelic Athletic Association results stopped. In 1958, the BBC broadcast a US program in which the Irish actress, Siobhan McKenna, was interviewed. She said that Ireland should not have been partitioned and that the IRA’s campaign of violence along the border was idealistic. Brookeborough described the broadcast as an insult to the people of Northern Ireland and that McKenna ought to be “put across someone’s knee and spanked.” The BBC withdrew the second part of the interview.

The DUP loves the chance to festoon the place with Union Jacks. One of its politicians recently proposed that the centenary of the foundation of Ireland in 1921 should be celebrated by a Festival of Britain like the one held in 1951, on the centenary of the Great Victorian Exhibition in 1851. It would be an opportunity, he said, to celebrate “the best of Britishness.”

Foster wears a big crown badge and lives in a bungalow close to the stately home of the late Brookeborough. She has more than a little of his lordly arrogance, behaving as if the people means the Unionist people. She is determined to push for Brexit on terms that would reinstate difficult aspects of a border that had lost much of its divisive potency, not least because of significant EU investment since the Good Friday agreement. The government helped the DUP to block scrutiny of the substantial funds it channeled into the Brexit campaign in England, in what was clearly a misuse of a special provision in the law relating to political donations in Northern Ireland.

The most significant relationship now is between Britain and Ireland, and it is not in good shape. In 1993, the British and Irish governments signed the Downing Street declaration. The prime minister, John Major, declared that Britain had “no selfish or strategic or economic interest in Northern Ireland” and that it would not stand in the way if the people on both sides of the border wished to consent to uniting Ireland. For its part, Ireland removed its constitutional claim to the six counties of the North. Until recently, only Sinn Féin pushed for reunification, and the bloody history of the IRA meant that many people shied away. But Sinn Féin has new leaders now who were not in the IRA, and in recent months the Taoiseach and his minister for foreign affairs have openly declared their desire to see a united Ireland within the EU.

A majority of people in Northern Ireland, including most nationalists, voted for remain. It is one thing for the DUP with its nostalgia for the days of empire and one-party government and candlewick bedspreads for the godly to ignore this reality. It is another for the British government. The prime minister’s unholy alliance with the DUP represents a return to selfish interest. The Good Friday agreement requires “rigorous impartiality.” May has responsibilities not just to the DUP but to all of the people of Northern Ireland and the Republic. This shabby alliance of Unionism and little Englandism might manage to get the UK out of the EU, but the price could be the end of the Union. With the DUP at the helm of the Titanic, a border poll on the issue of Irish reunification is looming like the iceberg.

- Susan McKay is the author of Bear in Mind These Dead, on the legacy of the Troubles