Patrick Maguire: Coming out of the darkness

Posted By: November 12, 2017

Patrick Maguire: Coming out of the darkness

One of the Maguire Seven, Patrick Maguire was only 13 when he was wrongly arrested along with his family for being behind the IRA Guildford and Woolwich pub bombings in 1974. Over the past 14 years, he has established himself as an acclaimed artist and tells Joanne Sweeney that he’s finally ready to embrace color in his work

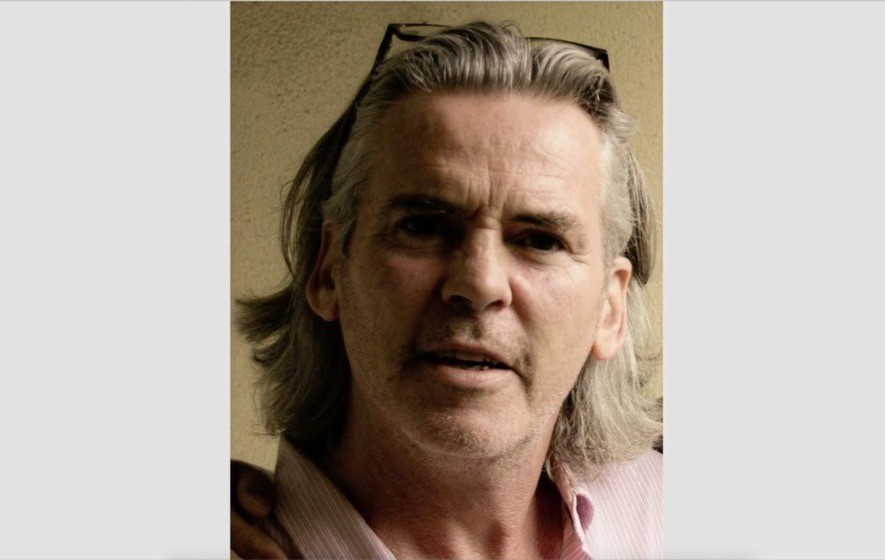

Artist Patrick Maguire, who was imprisoned

in England for five years as a child after being

wrongly convicted of terrorist offenses along with his mum, dad, brother, and uncles

Joanne Sweeney. Irish News. Saturday, November 11, 2017

Home, 2004, by Patrick Maguire. “At night-time, it seemed to me like I was in this dark cell in a red box Just the thought of it drained every feeling out of me” Picture: Courtesy Patrick Maguire

LIFE for Patrick Maguire was in black and white for a very long time but now at the age of 55, the artist says he’s ready for a life in color at last.

Maguire one of the Maguire Seven, a victim of one of the biggest miscarriages of justice in British legal history.

He was wrongfully imprisoned for five years from the age of 13, having been convicted, along with his parents Annie and Patrick Sr., his 17-year-old brother Vincent, his uncles Giuseppe Conlon and Sean Smyth and family friend Patrick O’Neill, of operating a bomb-making factory from their north London home, which was said to be the source of the explosives for the IRA Guildford pub bombings in 1974.

Maguire’s first exhibition of work in years, Out from the Darkness, will be open for viewing in London from next Wednesday and marks the end of what could be called his ‘dark phase’.

The darkness not only comes from the trauma of having his life turned upside down as a young teenager, separated from his mother, father, and brother and incarcerated in three separate prisons, but also specifically from a four-week period when, while still a child, he was kept in solitary confinement in a cell where a red security light was kept on through the night, every night.

Working in charcoal, pastels, and pencil, this stark new collection has a recurring image of a red box surrounded by black, which represents the unceasing red light.

“Every night this red light became so intense,” Maguire recalls. “During the day I would be scrubbing floors and the tears would flow.

“At night-time, it seemed to me like I was in this dark cell in a red box. If I wanted to lie down to cry, which was all I did, just the thought of that the red light got deeper and hotter and my breathing got worse. Just the thought of it drained every feeling out of me that I can only recognize now as an adult.

“As a parent, you know that moment when a kid does that open-mouth thing when they have caught their breath and you don’t know if they are going to cry or breathe? You just what them to make a sound – well, that was me every single night. The only thing they didn’t take was my soul, I have to believe that. And that soul was the child.”

“As a child of 14, I didn’t know that certain feelings had names for them as I do now. I didn’t understand any of the loss, the pain or that need, thinking ‘Where’s my mum? I want my mum, I want my dad: f**king Jesus God, where are you?'”.

Released from prison at the age of 19, Maguire went off the rails for a bit and got involved in a life of crime, drugs and drink while all the time police continued to take an interest in him, routinely harassing him for years while his parents still remained in jail.

Life had dealt him a bad hand; one that he has tried to make the best of ever since.

“When we got nicked that Thursday night, my world turned black and white, and color disappeared,” says Maguire in a strong London accent.

“What they did just cruel, absolutely cruel to a child. It saddens me but I’m here now and I have an insight into how a child feels and I can pass that on to someone who has more knowledge about it as I can say I’ve been there.

“It can be healed, even though I know I’ve got a bit to go. The cell will always be there, but not in that sense as it’s got no power over me. The door is wide open, I’m ready to go.

“Now that I’ve got this cell door open, I want to find some space and big pieces to paint on with loads of color. I just want to go for a walk as I’ve been contained far too long, physically, mentally, as one of the Maguire Seven.”

No bomb-making paraphernalia were uncovered by police in their home, but the Maguire Seven were convicted based on the discovery of what was claimed to be nitroglycerine on their hands and on coerced statements obtained from the Guildford Four, who included the now deceased Gerry Conlon, who was the son of Annie Maguire’s brother-in-law Giuseppe Conlon.

The forensic evidence was discredited on appeal in 1991 after a long campaign for justice; the seven had their convictions quashed and were released, and exonerated with a public apology from former Prime Minister Tony Blair in 2005.

Maguire made his peace with his cousin Gerry before he died, after he and Paul Hill of the Guildford Four had, under violent coercion from police interrogators, implicated his mother Annie as the ringleader of the alleged bomb-making unit. The Guildford Four were also exonerated after having their convictions quashed in 1989.

Last month he was at the London launch of Richard O’Rawe’s biography of Gerry, In The Name of the Son.

“We got together ages and ages ago, long before he died and embraced each other. A few words were said but that’s between me and him and we hung about and all was good.”

Maguire has told his story in art, words and on stage; in 2009 his critically acclaimed memoir My Father’s Watch, written with Carlo Gebler, was published. It was adapted into a play and staged in Belfast in 2013.

He considers himself a self-taught artist, who discovered the healing power that art therapy can bring to a person’s trauma when he was treated at the Priory Clinic in 2004.

Once he began drawing, he drew hundreds of dense, dark grey pictures at a time. He never stopped after that and says he works seven days a week on his art now.

Describing himself as “bipolar and having manic behavior,” Maguire has found solace in his art and his family. He sees his mother regularly and both live a short distance from their old home. He has an adult daughter and two adult sons and a four-year-old boy, along with four grandchildren.

But his recent coming to terms with his time spent in prison through art has been at a huge personal cost – he says he needed to distance himself from his youngest child in order to work through his trauma.

Maguire is currently collaborating with East West Artisans (Asia Art Therapy), an organization which brings art to autistic children in China; a portion of his exhibition proceeds will fund a further trip to Singapore and China.

He says: “I’m not a book reader but I love quotes as they are like a light stroke of a brush with color to me. Picasso said, ‘You do not make art, you find it.’ Well, f**k me, Pablo, I’ve found a load. Now it’s as if a light has gone on inside me, with a rainbow.

“For me, my art will be like the child sitting on my shoulder and we are going to paint big canvasses in color. What I’ve found is that as the darkness has left, the light that is shining in now means that I’ve got untold work to do.

“I’ve always known that I had that in me but before it was all the dark stuff.”