Fight for civil rights 50 years ago changed the North forever

Posted By: October 08, 2018

Fifty years ago, civil rights marches took place in Derry, Belfast, and Armagh. Activists wanted equality, but what happened next changed the North forever, writes Anthony Coughlan

Anthony Coughlan. T-Irish Examiner. Cork. Saturday, October 6, 2018

Fifty years ago, civil rights marches took place in Derry, Belfast, and Armagh. Activists wanted equality, but what happened next changed the North forever, writes Anthony Coughlan.

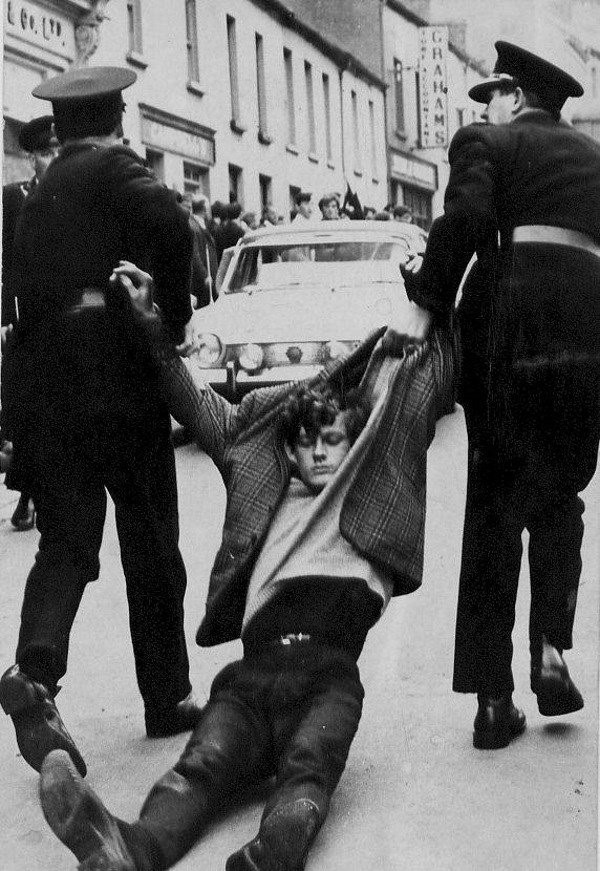

The TV pictures of the police batoning of civil rights marchers in 1968 on Duke St, Derry, brought the anti-Catholic discrimination that then existed under the Unionist-majority regime at Stormont to the attention of the world.

The images showed Westminster MP Gerry Fitt with blood on his shirt. Three British Labor MPs were beside him in the frontline of marchers.

These events, 50 years ago, made clear that Labor prime minister Harold Wilson’s government in London would have to insist on reforms in what some at the time called “Britain’s political slum.”

Although there is a library of books on the 1970-94 military campaign of the Provisional IRA and Loyalist reaction to it, there isn’t a single one that does justice to the different elements of the complex civil rights movement that preceded it.

Image from the 1968 Derry march

I, myself, was an observer at the founding conference in Belfast in 1967 of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA), which sponsored the first civil rights marches.

I walked from Coalisland to Dungannon on the first march in August 1968, which resulted from MP Austin Currie’s protest at local housing discrimination.

I was also in Duke St, Derry, on October 5. Ten years earlier, I had been active in the Connolly Association when I lived in London from 1958 to 1961, as the association set out to expose the civil rights abuses in Northern Ireland in British labor and trade union circles.

But what were those abuses? The Westminster Government of Ireland Act partitioned Ireland in 1920. Northern Ireland nationalists, overwhelmingly Catholic, suffered under Unionist majority rule at Stormont for the next 48 years.

Majority nationalist towns like Derry, Enniskillen, and Dungannon were gerrymandered to ensure permanent Unionist control. Multiple votes for ratepayers in local elections facilitated this.

Hence the Civil Rights call for one man, one vote. Anti-Catholic discrimination was widespread in allocating council housing and in public and private employment.

Flying the Irish flag was illegal. Republican clubs were banned. Stormont’s Special Powers Act permitted to arrest without warrant, imprisonment without trial, and the banning of nationalist publications and meetings.

The auxiliary B-special constabulary allowed volunteers in this wholly Protestant force to intimidate their Catholic neighbors at will.

A young student is dragged away unconscious along Duke St. after police

attacked and refused the civil rights marchers to proceed across

Craigavon Bridge, to the city center.

In 1949, Britain’s post-war Labor government passed the Ireland Act, which provided that there would be no change in the constitutional position of the North without the consent of the Stormont Parliament [not just the consent of The North’s majority].

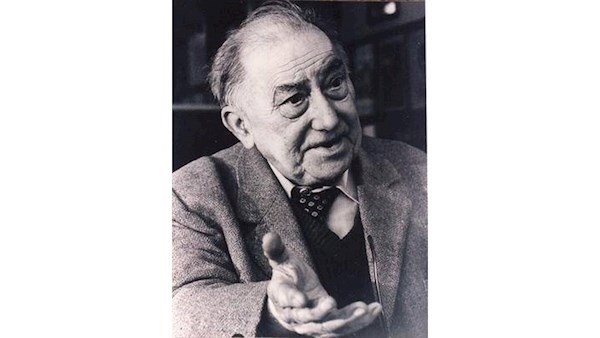

Twenty years later, in 1969, Harold Wilson was under heavy pressure from his backbenchers to reform the place [The North]. It was primarily the work in Britain of the Connolly Association (CA) and the historian Desmond Greaves (1913-1988), editor of its monthly paper, The Irish Democrat, that was responsible for this change.

This aspect of the civil rights movement has been neglected by historians. Yet it was vital to the outcome.

The CA, which is still going strong, was founded in 1938. In 1955, it adopted its modern constitution which set its objective as winning the support of the British labor movement for ending partition and ensuring that as long as Britain ruled The North, the people living there should have the same civil rights as people elsewhere in the UK.

In 1958, the association sent British barrister John Hostettler to cover police maltreatment of two Republicans, Mallon and Talbot, who were on trial in Belfast.

It published a pamphlet in which Hostettler described his impressions. Over the following two years, Hostettler and various CA activists, including myself, spoke at numerous British Labor Party and trade union branches about the misdeeds of the Stormont regime.

The Connolly Association then launched a campaign to draw attention to the fact some 200 Republicans were interned for years, without charge or trial, in Belfast under the Special Powers Act, following the IRA’s 1950s border campaign.

It organized a series of telegrams to Unionist prime minister Basil Brooke calling for their release.

By 1961, over half of Britain’s parliamentary Labor Party had signed these. This was years before any civil rights agitation stirred in the North itself.

This work is documented in the Irish Democrat, which is available on the internet.

Image from the 1968 Derry march

While Greaves was a member of the Communist Party, which perhaps explains the slowness of historians to acknowledge his work, the bulk of the CA’s membership was non-party, as I was myself.

It was Labor Party members of the association who founded the Campaign for Democracy in Ulster in 1965 to help spread the anti-Unionist message inside Labor.

When Dr. Conn and Patricia McCluskey set up the Dungannon-based Campaign for Social Justice in 1964 and began documenting in detail the civil rights abuses in The North, the Connolly Association spread their material in British Labor and progressive circles.

The Association was affiliated with the National Council for Civil Liberties, an influential body in 1960s Britain. This “leveraged” its anti-Unionist message.

In November 1966, Northern prime minister Terence O’Neill personally sought to defend his government’s position in a response he made to a memo from the CA’s standing committee documenting the abuses he presided over.

The outcome of this work meant that when Gerry Fitt was elected MP for West Belfast in 1966, he was welcomed by a cohort of Labor MPs in the House of Commons who wanted Stormont reformed.

In The North itself the following year, 1967, the foundation of the NICRA resulted from the coming together of two ideological elements: The politicizing republicans of the 1960s who had come to realize the impracticality of trying to unite Ireland by force, and the trade unionists of the Belfast Trades Council, some of them left wing but of Protestant background. NICRA’s demand was British rights for British citizens.

Desmond Greaves: Editor of the Connolly Association paper,

‘The Irish Democrat.’

It did not raise the partition question. All shades of Northern political opinion were represented on its first executive: Labor, Liberal, Nationalist, Republican, and Communist, including a Unionist who was co-opted.

Following the Coalisland-Dungannon civil rights march in August 1968, and the Derry one on October 5, in November the Derry Citizens Action Committee, led by the Catholic John Hume and the Protestant Ivan Cooper, marched thousands of people peacefully into Derry city center, so establishing their right to peaceful protest in their own city. This was the culmination of the non-violent phase of the civil rights movement.

In December 1968, Unionist prime minister Terence O’Neill, caught between the local Civil Rights Movement on the one hand and Harold Wilson’s government on the other, conceded most of NICRA’s demands.

The NICRA executive responded by calling for a moratorium on marches to give time to see what the reforms amounted to.

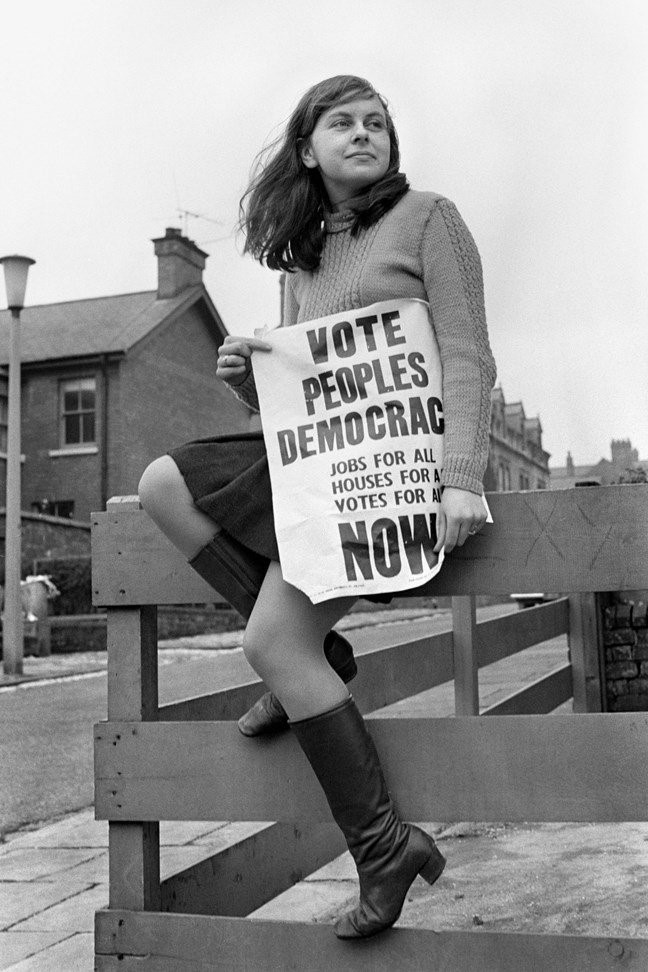

It was in this context that the left-wing students of the People’s Democracy, led by Eamon McCann, Bernadette Devlin, and Michael Farrell, staged the march from Belfast to Derry in January 1969 that was assaulted by Paisleyite Loyalists at Burntollet.

The Cameron Commission Report, which is still the best account of the early civil rights period, characterized the Burntollet march as a coat-trailing exercise across the province.

The students’ courage was undeniable, but their actions helped raise the sectarian temperature.

Bernadette Devlin: One of the students who led a march in January 1969.

The People’s Democracy call for socialist measures as well as civil rights ones also caused division in the movement.

A People’s Democracy march in Newry that January saw marchers hijacking police tenders while the police looked on. Initial Protestant sympathy for the civil rights demands was now disappearing rapidly.

People’s Democracy leaders Michael Farrell and Kevin Boyle were then elected to the NICRA executive at its third AGM. They proposed holding an unstewarded civil rights march to Stormont going through Protestant East Belfast.

This precipitated the resignation of three of the more moderate members of the NICRA executive, including Betty Sinclair, the full-time secretary of the Belfast Trades Council. The proposed march was then called off. More experienced than the student radicals, the moderates knew the sectarian demons that were awakening.

O’Neill, the prime minister, was under attack from Unionist hardliners in his own party and he resigned in April 1969. There followed the attacks by Loyalists on Belfast Catholic areas in August 1969. This led to the disastrous Republican split in January 1970 and the formation of the Provisional IRA, which embarked on a military offensive against the British Army.

By 1971, the Civil Rights Movement was wholly sidelined. British and international opinion, which three years before had been behind the non-violent civil rights marchers, now saw the Northern problem as one of “containing IRA terrorism.”

There followed the quarter-century-long military campaign of the IRA, until a new generation of Northern Republicans, led by Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness, ended this in 1994.

A civil rights march in Derry in January 1969.

Michael Farrell with a bullhorn

The IRA’s “armed struggle” generated new divisions between Northern Protestants and Catholics. The ultimate responsibility for the violence, however, must lie with successive British governments that let the Northern Ireland civil rights abuses fester undisturbed for decades.

The 1998 Good Friday Agreement is a commitment to a regime of “equality of treatment and parity of esteem” between Northern Catholics and Protestants. Essentially this is “civil rights redivivus.”

Equality of treatment and parity of esteem are the only basis on which the possibility exists of Northern Unionists rediscovering, over time, the political implications of the common Irishness they share with their nationalist fellow countrymen and women.

That is the only way in which a United Ireland can ever be attained.

Anthony Coughlan is associate professor emeritus in social policy at Trinity College Dublin. He was a student at UCC from 1953 to 1958 and is the literary executor of the estate of the historian Desmond Greaves

Bottom of Form